Post by glactus on Sept 17, 2011 2:02:53 GMT

Soviet nuclear thermal propulsion was initially pursued as an alternative to nuclear electric propulsion. It was a late 1950's design for missiles and launch vehicles using nuclear thermal engines with ammonia as propellant.

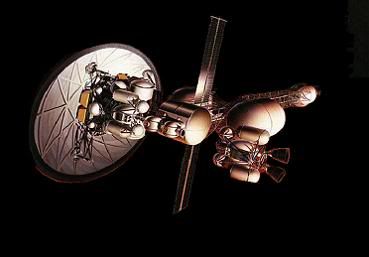

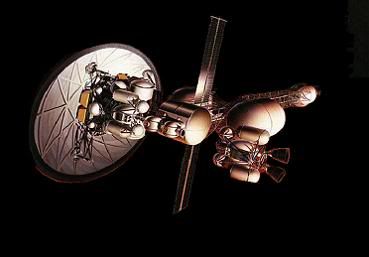

The nuclear thermal propulsion system

The engine bureaux of Bondaryuk and Glushko continued study of nuclear propulsion, but using liquid hydrogen for upper stage applications. Engines of 200 tonnes and 40 tonnes thrust with a specific impulse of 900 to 950 seconds were being studied

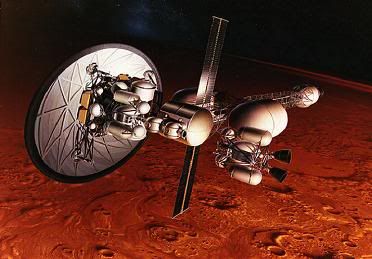

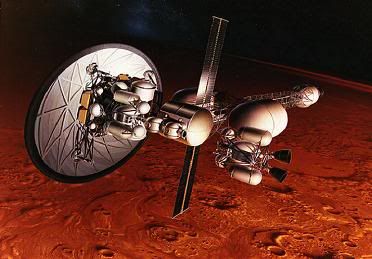

Nuclear spacecraft at Mars

For a Mars expedition, it was calculated that the AF engine would deliver 40% more payload than a chemical stage, and the V would deliver 50% more. But Korolev's study also effectively killed the program by noting that his favoured solution, a nuclear electric ion engine, would deliver 70% more payload than the Lox/LH2 stage.

Looking at the nuclear spacecraft

This exotic technology, also pursued in the United States, would have resulted in a 200 tonne thrust engine with a specific impulse of 2000 seconds. Although the draft project was completed and it was concluded the concept was entirely feasible, no funds for development were forthcoming.

It was not Glushko or Bondaryuk, but the Kosberg OKB that took concrete steps in the 1960's toward actually building nuclear thermal propulsion system hardware. In 1962 Kosberg, together with the Kurchatov Institute, Keldysh Scientific Centre, NPO Luch, and a half dozen other institutes, began experiments with nuclear thermal rockets for upper stage applications that used liquid hydrogen as the propellant.

Soviet development of nuclear-thermal propulsion continued. , NPO Luch began tests of prototype Kosberg engines at a test stand 50 km Southwest of Semipalatinsk-21 in 1971. Tests continued there through 1978. Simultaneously a more elaborate facility was built 65 km south of Semipalatinsk-21 for comprehensive tests of the Baikal-1 prototype engine.

Thirty simulated flights were conducted from 1970 to 1988 without failure. It was eventually proposed that two engines would be derived from this work: the RD-0410, a 'minimum' engine, of 3.5 tonnes thrust; and later the RD-0411, a 70 tonne thrust engine.

By 1989 work on both nuclear electric and nuclear thermal propulsion included bimodal use of the nuclear reactors to provide electrical power during dormant or ballistic cruise phases of flight. A nuclear thermal Mars spacecraft proposed by the Kurchatov Institute in 1989 featured a new design with a powerplant of 20,000 kgf, a thermal power of 1200 MW, operating time of 5 hours, and a specific impulse of between 815 and 927 seconds.

The collapse of the Soviet Union ended further development work on nuclear thermal propulsion.

Credits:These are non copywrite images

Text by Wikipedia

Space art by Glactus

The nuclear thermal propulsion system

The engine bureaux of Bondaryuk and Glushko continued study of nuclear propulsion, but using liquid hydrogen for upper stage applications. Engines of 200 tonnes and 40 tonnes thrust with a specific impulse of 900 to 950 seconds were being studied

Nuclear spacecraft at Mars

For a Mars expedition, it was calculated that the AF engine would deliver 40% more payload than a chemical stage, and the V would deliver 50% more. But Korolev's study also effectively killed the program by noting that his favoured solution, a nuclear electric ion engine, would deliver 70% more payload than the Lox/LH2 stage.

Looking at the nuclear spacecraft

This exotic technology, also pursued in the United States, would have resulted in a 200 tonne thrust engine with a specific impulse of 2000 seconds. Although the draft project was completed and it was concluded the concept was entirely feasible, no funds for development were forthcoming.

It was not Glushko or Bondaryuk, but the Kosberg OKB that took concrete steps in the 1960's toward actually building nuclear thermal propulsion system hardware. In 1962 Kosberg, together with the Kurchatov Institute, Keldysh Scientific Centre, NPO Luch, and a half dozen other institutes, began experiments with nuclear thermal rockets for upper stage applications that used liquid hydrogen as the propellant.

Soviet development of nuclear-thermal propulsion continued. , NPO Luch began tests of prototype Kosberg engines at a test stand 50 km Southwest of Semipalatinsk-21 in 1971. Tests continued there through 1978. Simultaneously a more elaborate facility was built 65 km south of Semipalatinsk-21 for comprehensive tests of the Baikal-1 prototype engine.

Thirty simulated flights were conducted from 1970 to 1988 without failure. It was eventually proposed that two engines would be derived from this work: the RD-0410, a 'minimum' engine, of 3.5 tonnes thrust; and later the RD-0411, a 70 tonne thrust engine.

By 1989 work on both nuclear electric and nuclear thermal propulsion included bimodal use of the nuclear reactors to provide electrical power during dormant or ballistic cruise phases of flight. A nuclear thermal Mars spacecraft proposed by the Kurchatov Institute in 1989 featured a new design with a powerplant of 20,000 kgf, a thermal power of 1200 MW, operating time of 5 hours, and a specific impulse of between 815 and 927 seconds.

The collapse of the Soviet Union ended further development work on nuclear thermal propulsion.

Credits:These are non copywrite images

Text by Wikipedia

Space art by Glactus